INTRODUCTION:

Following

the recommendations of Bradford Garton and Fred Lerdahl, I will not be

submitting scores, and have instead included a essay that describes my ideas

and work

with links to sample recordings and documentation. As an artist who rarely

uses notation as the basis for compositional ideas, I know I am

an untraditional applicant; consequently, I have chosen to give the program

a

sense of myself and what I can offer through a sampling of pieces recorded

over the last ten years, as well as through a conceptual discussion of

my work both past and present. My CV should you be interested is here.

As a self-taught composer with a successful career in music as well as visual

and performance art, I have toured extensively and had several solo shows

throughout the United States and Europe, and am currently represented by

the Mountain

Fold Gallery in New York City. I have released seventeen full length albums

under the name mudboy, along with dozens of smaller releases done as collaborations

with other artists, or as producer. My sense of composition remains extremely

broad, and the work that I have created ranges from autogenerative computer-assisted

scores to mighty Wurlitzer pieces; audio collage and field recording to

performative touring concerts ; immersive installations to kinetic

light paintings. The

media changes, but the fundamental idea—that composition is a tool

for the organization of non-literal, often unconscious experience—remains

the same. I remain committed to themes of perception, fractal organization

and living systems in their relation to cognition and experience. These

are the ideas I wish to continue researching in regards to composition

at Columbia, where I hope to study and produce challenging

music.

After many years of working almost exclusively within the world of experimental

and so-called underground music, I now recognize that, in order to become

a more sophisticated and fully-evolved composer, I must refine my abilities

in

classical forms and traditions of orchestration. Specifically, I want

to transform, or perhaps repurpose, the conceptual frameworks inside

of which

I have created

largely electronic pieces and apply them to conventional principles of

notation, while working in collaboration with contemporary ensembles

of traditional instruments.

I. WORK, 1996-2008.

For the duration of the 1990s, I rarely touched a musical instrument.

Nonetheless, I was always drawn to sound, and much of my late teens

and early twenties

were occupied with field and found recordings, as well as the manipulation

of sounds using the format of the cassette tape. The result of this wide-ranging,

if irregular, work was the origin of an audio "zine" compilation

series entitled Free Matter for the Blind.

Sample

of combined excerpts from issue 2 "Farewells to Summer"

This series stretched through ten issues into early 2004 , and would eventually

become the basis for a record label by the same name.

With Free Matter for

the Blind, I have released albums including material such as straightforward

field recordings, experimental music, audio magazines, soundtracks to theater

pieces, and experimental computer work. In 2008, Free Matter for the Blind

was selected by the pioneering radio station WFMU to be an official curator

of its online free music archives. Most the label's out-of-print albums are

included in that archive.

When I enrolled in college, I knew nothing about alternative sound techniques

or practices; indeed, the strangest musical work with which I was familiar

was the spoken-word recordings of punk musician Jello Biafra, along with

some narrative or storytelling sections of the odd Bauhaus record. All

this changed when I began studying at Brown University, where I worked

with music

professor Todd Winkler in Brown's multimedia lab. Brown introduced me to

the likes of Stockhausen, Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros, Laurie Anderson

and, most significantly, John Cage. I began to understand my work primarily

in musical terms, and to consider the act of composition itself as an aesthetic

practice. Though I continued to pursue alternative media forms , moving

away from two-track cassette and relying on computer programs to edit and

arrange,

I became increasingly interested in pushing the generic boundaries of music,

and, in particular, the potential for using artificial intelligence (in

the form of midi based MAX patches) to compose complex and sophisticated

pieces.

As may be clear, music, to my mind, remained a conceptual practice independent

from performance with "real" or regular instruments.

Several important compositions emerged from this period, one of which, "A

TOMY Holiday Album," was eventually released as limited edition CDr.

This piece features the live recording an automatically-composed (MAX), midi-triggered

orchestra. The tempo of the piece rises steadily over the seventy minutes of

the piece, whose final movement features the structural collapse of the individual

sounds, as the processor finds it cannot handle the increased demands of the

software, and ultimately crashes.

Sample

of the generative TOMY Holiday album

Sample of the last movement

After leaving the university, I became less enamored of using computer

software to generate music, though I continued to work on the audio zines

of Free

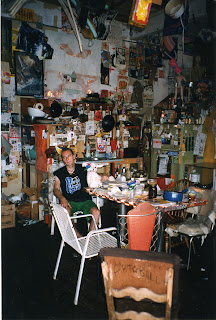

Matter. In 2000, I began living and working in the celebrated Fort Thunder

artist's collective in Providence , Rhode Island.

At the time, Fort Thunder

was perhaps the most

important underground music venue in the United States. It was

from this community that much of the early "noise" culture of

the early 2000s emerged, as experimental sound production and musical performance

was combined

with the visual art and printmaking practices of silkscreen and

poster

work.

The

multimedia artists Dear Raindrop, Forcefield, and Paper Rad

are all associated

with the cultural impact of Fort Thunder, as are critically-acclaimed

bands like Lightning Bolt, Black Dice, SEG, and Lucky Dragons,.

The

multimedia artists Dear Raindrop, Forcefield, and Paper Rad

are all associated

with the cultural impact of Fort Thunder, as are critically-acclaimed

bands like Lightning Bolt, Black Dice, SEG, and Lucky Dragons,.

Despite Fort Thunder's acceptance by an international audience, those

of us who lived there were most passionate about its roots as a

home for

artists and musicians inspired primarily by the political cultures

of anarchism and survivalism. Aesthetically, I would say we were interested

in the discarded flotsam

of

late capitalist civilization, and it was from there that we took

both our

inspiration and our materials: my world was filled with bright

trash, analog synths, and toy instruments. Computers, which were fragile,

temporary and

expensive, were looked down upon and so, simply, not around. I

was

still fascinated, however, with the creative potential of autonomatic

composition,

and so began to pursue the idea of interaction with the idea of

computers, rather than with the machines themselves.

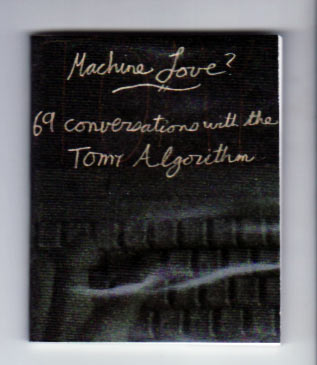

Several “TOMY” Projects

resulted from this field. TOMY, essentially, was a human performing a machine-like

intelligence in a calculated and moving attempt to be human—the

absolute inverse of a customer service representative, a human

restricted to the

highly scripted behavior of a computer .

The Turing test became

a centerpiece of

this period, and having a space like Fort Thunder, which regularly

filled up with people, allowed me to test some of these ideas out

in a public

arena. The TOMY projects were generally a series of interactive

installations, sometimes

posing as video games, sometimes as simple illusions of pre-recordings.

Much of the work was accomplished through remote video and audio

cameras, while

at other times fortune-telling or video game like machines were

built with human individuals inside.

Documentation ranged from video, to generated text files

played as videos in Quicktime , and even the publication of a small book

of receipts

chronicling

the results of one of the oracle machines.

While I continued working

in sound composition, I was still not playing instruments; I was,

however, playing

video games.These games were controlled using a two-handed keypad

and about

a dozen different buttons, one (at least) for each finger. To succeed

at the game, one must be able to punch complex strings of code

out using these

buttons, working in a kind of strange, unconscious rhythm.

I would often look down at my hands and find myself surprised at the complexity and speed of their automatic motions, thinking that if they could be applied to a keyboard, rather than a keypad, something truly compelling, and different, might emerge.Using an old Hammond organ in the back of Fort Thunder, I stopped playing Street Fighter and became mudboy.

In these early days of working as a musician, the early minimalist

composers I had studied as an undergraduate remained in the

back of my mind, while

life at Fort Thunder put me shoulder to shoulder with contemporary

experimental musicians who were releasing their music using

CDr and cassettes. Originality

and creativity were my personal objectives, and though I

continued to be impacted by Raymond Scott, Terry Riley and Nobukazu

Takemura,

it was the

culture of this revolutionary space that provided me with

the intellectual permission to discover a language of my own design.

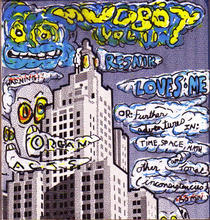

The second series of mudboy recordings, inspired by the awkward collapse

of simple mathematical arpeggiating circuits built into the organ itself-

against the irregular playing of a human new to the keyboard became, mudboy

Volume II- Or Further Adventures in Time, Space, Math and Other Tonal

Inconsistencies, and was

released in 2001.

Track

5:"Flee- Fleet!" (2'10)

In the beginning, mudboy was simply a recording project,

using the Hammond organ and a four-track recorder. I

would return again

to the

looped sounds

that had marked the automatic composition of my earlier

works on MAX, but for now I was playing live, improvising

within

the framework of

public performance and with a variety of electronics

and looping effects. My intellectual interests drew me to the parallels living

systems, including ant farms, traffic patterns and animal

migration routes.

As a composer, I

developed ideas and images derived from my personal research

into forms of music that were circular systems of sounds,

without too much emphasis

on

the notion of sequence or temporal development. This

densely atmospheric mode of composition still marks my

present work,

which focuses on the

narration of movement through described landscapes and

the negotiation of sonic events.

Much of this work was compiled in 2004 for the Last Visible

Dog label.

Track

7: LOST (8'10)

Track

7: LOST (8'10)

Later I would begin tinkering with the Hammond organ,

increasing my palate of sounds; eventually I would take

a circular saw

to it, cut

it in half,

and bring it on tour.

I also brought my laptop, with its MAX program,

on tour, but (unlike the Hammond), it did

not survive. Realizing

that the

computer was

too unreliable

and fragile a machine to be used as an

adjunct in

live performance, I began to consider it

only as a compositional

tool in the

creation of

multi-track

recordings; as a result, I began to think

of my musical pieces as a form of sculptural or filmic

activity, in

which large amounts of

source

material

are sorted and gradually reduced into

smaller, more concise moments. My experimental sound

work with

Free Matter

for the Blind began

to leak into

the mudboy compositions,

Solitron Wave (5'14)

In 2005 I produced a series called "The

Haunted Cobblestone Sunset Concert Series.”

Although

I had begun to use field recordings in my life performances

and on the

mudboy albums, I now

wanted to

create a situation

in which live,

unrecorded, and unpredictable sounds

could be layered

onto the arc of a live performance.

The Haunted Cobblestone series was,

accordingly, a ten- part performance series in which

invited musicians improvised

live out of an open

window. The musicians could not be

seen by the audience, which was seated on

the street below where it would be

confronted with passing cars, playing children,

and neighboring songbirds. Each performance

would begin

in

the early evening one hour before

sunset, so that its final moments

would coincide

with those

of the setting sun.

Musical elements

included acoustic accordion activity (Exerpt:

Alec Redfearn),

triggered

samples and looped

guitar, (Excerpt:

Area C),

to an 9-11

anniversary performance

which featured the occasional burst

of AK47 gunfire at actual volume ricocheting

down

the street,

accompanied by the live

sound of a

sledgehammer dismantling

a handful of electronics and furniture.

(Excerpt:

Jason McGill),

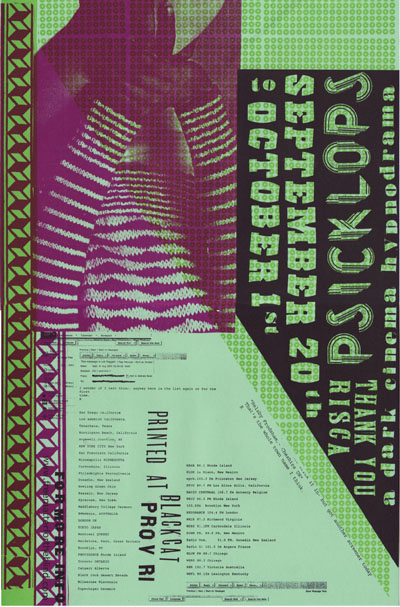

This was followed by the release

of Psicklops, an investigation

of what

I characterized as "dark

cinema," and

the production of a point-of-listening

perspective in sound-only

narratives. Psicklops hoped

to begin to develop

counter-possibilities to

Marcel Duchamp’s

provocative statement, “It

is possible to show someone

looking, but

you cannot

listen to

someone. ”

In traditional cinema,

"the gaze" or watching

someone look, is the fundamental

semiotic

basis for the

creation of the

illusion of perspective

through space

and time; Psicklops

asked if the same ends could

be achieved

in

a narrator-less

audio

narrative.

Conceived

as a contemporary adaptation

of

Kafka’sThe

Trial, Psicklops

used a

multi-textured

collage

of found

sounds,

guerilla

field

recordings,

sampled

creative

common

works,

studio

actors,

and

experimental

electronics

to

create

a one hour

long operatic

experience

in which

the audience

is treated

not just

as

an outside

observer,

but

complicit

in,

and anticipated

by, the

work

itself.

With support

from

the Rhode

Island

State Council

on

The Arts,

I

experimented

with distributing

the piece

as

a film,

and screenings

were arranged

so

that an

audience

could appreciate

the work

as a self-contained

recording

in a

darkened

room. These

screenings

were held

over

one week

in over

50

locations

around

the world

with a

series

of

international

transmissions

involving

two

dozen

radio stations.

Excerpt

1

Excerpt

2

Excerpt

3

Later that

year,

I received

a

grant

by the Rhode

Island

Arts

Council to write

a series

of pieces

for the

Mighty

Wurlitzer

Theater

Organ,

one of

which

was housed

at the

Performing

Arts

Center in

Providence.

Historically,

the Center's organ

has only

been used

to play either

pop concerts

or traditional

music to an older

audience. The

grant allowed

for a free concert

of experimental

compositions and

was geared

toward a

younger group

of individuals who might

otherwise only

listen to music

in clubs and parties.

For me,

the appeal of the

instrument was

that unlike

contemporary keyboards,

which assign

a complex

sound to one

set of

keys, the pipe

organ had

five keyboards,

each of which could

be assigned to their

own set of

sounds. I

was able to play

patterns on

one set of

keys while an

assistant manually

pulled stops

to allow

for a constantly evolving

sound. In

addition, because

it was a theater

organ— intended

for accompanying performances and films—, it allowed for the incorporation

of a great number of percussive and non-musical elements. In many ways, it

was the ultimate analog acoustic noise instrument. The recordings were released

by the magazine The Sound Projector a few years later.

Desert

Things (6'47)

Solo

Work

Better

Left

to

Feet (5'59)

Wonder

Show of the Universe(14'16)

The experience of working on the Wurlitzer inspired the creation of the “mudboy mini," an electroacoustic keyboard built around an integrated harmonium and yamaha synth.

In

2007, I

would enter

a transmission

arts residency

at the

radio station

Free103.9 to

study the

history and

possibilities of

traditional radio

theater. My

goal was

to develop

a concise

semiotic theory

around the

idea of

a sound-based

narrative perspective,

one that

would be

as robust

as the

one I

studied as

a film

student at

Brown. The

result of

my research

at Free103.9

was a

decision to

move away

from film's

emphasis on

the gaze

as the

ground of

perspective—what

Duchamp called “looking at looking”—and towards an understanding

of listening, in particular guided listening, as a fundamentally hypnotic

and therefore expansively proprioceptive event.

This

study encouraged

me to

explore

the potential

for using

the voice

as both

a conduit

for semantic

information

and as

a means

of orienting

the audience

towards

a particular

and peculiar

experience

of listening

estranged

from

verbal

or linguistic

communication.

Relying

on the

manipulation

of the

extra-semantic

signifiers

of speech—including

affect,

intonation,

and

various

modes

of prosodic

experimentation—,

my

work

from

this

period

attempts

to

create

musical

phrases

that

submit

the conventions

of speech

to a

provocative

deformation

.

Taking

my cue

from scientific

studies

on

cognition

and

audio

perception,

which

remain

fundamental

guiding

influences,

I

began

to

experiment

with

the

spectrum

of

the

spoken

word

from signifier

to

musical

phrase.

This

took

the

form

of

several

pieces, the

following

is

from

my

LP

entitled “Let

It

Be a

Nightingale

Then.”

The first track, Instructional

Video for This Side (6'46)counterposes

two sets of indecipherable language, one human, and the other avian.

Meanwhile,

in "Mudmantra for Conquering Death," a video installation with

Dave Fischer using generative video software, three layers of language are

used, some, none, or all of which—depending on the language background

or skills of the listener—may

be

intelligible.

Mudmantra

video *80 megs- load, (4:00)

Mudmantra

audio only

These

theories

paralleled

my

refinement

of

the

mudboy

live

performances,

which

were

increasingly

anchored

around

my

sense

that

music, language and focused group attention are a

tool

for

the

creation

of

what

I

refer

to

as

a “human state change.” The

operative

metaphor

for

this

new

kind

of

work

was

derived

from

occult

histories

of

magic

and

spellcasting,

and

of

the

shamanic

tradition

of

the

composer

as mediator

between

the

conscious

and

unconscious

mind of

the

audience.

My performances, some of which used firecrackers as sound elements, along with any number of lighting effects- created a fully immersive experience for the audience described by online journalist Nate Dorras follows:

One by one the lamps and droplights are doused, and the stars

come out.

Through the vapor of a weakly sputtering fog machine they wink, deep blue

pinpricks atop the non-invisible speaker tower and strewn across the floor

before the seated audience.

There is an all-encompassing chorus of insects. Perhaps frogs. Night sounds.

Vague illumination is provided by the diffuse glow of the windows and a trio

of candles arrayed around a custom-built wood-housed organ, but the scattered

stars most draw the eye. As well as, by their barest gleam, the dim form

that picks its way between, swinging a bunch of smoldering incense like a

somnambulant priest bearing a censer. Organ notes cycle blankly against the

swirl of natural sound. "Each life, a light." The air is sweet

and smoke-embellished...

His eyes blink bitter red. With a lunge, we are suddenly blinded. There is

a roaring in our ears, vision swims to make sense. As he spins, we see: he

grasps one of the droplights, turning its harsh light directly down on us as

he calls out again. And then he is swinging that light by its cord. A comet

arcing just over our heads. The audience is transfixed, or I am; I am no longer

aware of them around me. And then the roar breachs and falls away, the light

dying, all easing out more careful organ sequences and wearied, stumbling drums.

Text by Nate Dorr: February 06, 2009

http://www.imposemagazine.com/photos/mudboy-at-silent-barn .

One

of

these

performances,

a

live

session

at

VPRO

radio

in

Amsterdam,

was

recently relased

by

the

prestigious

Staalplaat

label in a folded wooden box.

. Excerpt,

3 min

Excerpt,

3 min

In

2008,

the

album Hungry

Ghosts! – These

Songs

are

Doors

was

released

by

NotNotFun

as

an

LP,

before

being

re-released

by

Digitalis

Industries

later

that

same

year.

Hungry

Ghosts! was

constructed

in

such

a

way

as

to

invoke

as

the

cognitive

state

of

a

waking

or

lucid

dream:

each

song

was

a

new

vision,

buried

inside

the

other.

By

now,

all

the

recordings

on

the

album

were

taken

from

computer

compositions,

the

product

of

slicing

and

re-arranging

many

sessions

and field

recordings

to

create

a

complex

whole.

Shockwave track 7 (4:22)

RECENT WORK

My recent work is a response to the conviction that, as Peter Brown puts it in

The Hypnotic Brain, “the neurobiology of hypnosis overlaps with the neurobiology

of music.” The dissociation critical to hypnotic phenomena hinges upon

a disengagement of a critical aspect of consciousness. That disengagement is

generally accomplished through a kind of distraction, and through the entrapment

of an irresolvable field of change and motion that nonetheless hints at a kind

of resolution, however compromised.

While we can easily imagine a slightly swinging watch, or the shadow of a flickering

candle flame to accomplish this distraction, there are clear similarities between

the techniques of trance induction and many kinds of even traditional and classical

music; and that furthermore there is a close affinity between this irresolvable

field of change and the disassociative effects of certain natural and chaotic

shapes in nature.

The project of composition that arises from these theoretical interests is not

so much a literal re-interpretation of organic processes as inorganic sound—resulting,

say, in a Max/MSP-generated invocation of a coastline, or flocking gulls—but

rather the negotiation of a synaesthetic relationship between the branching pattern

of certain trees, and of those of serial music. The compositional results of

these investigations are exemplified in the piece “Swamp Things,” which

exists currently in two versions:

the

first is played live on the Wurlitzer (14'16) in

the previously mentioned concert,

and the

second is an electronic recording

using

circuit bent keyboards and effected guitar.(9:29)

As in most of my work the specific instrumentation is second to the conceptual

framework.

The same basic organizing principles govern the The Black Creek track from an

upcoming LP that is the first of a series entitled mudboy’s Impossible

Duets. The Black Creek is conceived as duet between myself and the creatures

of the bog near my family’s farm in upstate NY.

(3

min excerpt)

Of course, this notion of the “shape of nature," which mediates these newest compositions, is-in mathematical terms- a conversation about fractal organization. As the granular manipulation of time and duration within a sample or musical phrase became easier on account of advances in computer software, it has become possible to organize a piece of electronic music without regard to tempo and only in regard to "shape". If music is, theoretically, effective because of its internal structural relationships, and if those relationships were organized in such a way as to remain visible through different extreme variations in tempo, we may begin to create a truly fractal piece of music – one which could be played at any number of speeds and still manifest the same motifs and relationships.

Early explorations of these possibilities inform my most recent projects. Released

on 7" vinyl, Music for Any Speed, uses a record player as

a performer in collaboration with the owner of the record. The album was

a looping

bi-faced composition;

one side, Thaw,(4'32

at 33rpm)

expressed an exuberance and almost impossible rapidity

which devolves into

Freeze, (6;20

at 33rpm)

the reverse side of the album that turns the same notation

in a frozen wasteland, built around a granular representation of the first

track and then back again. Ideally, the two pieces could be played at any

speed, one right after the other, seamlessly, without beginning or end.

My interest in fractal living systems as an organizing creative principle

has had its analog in the installation and art work I continued to do in

the gallery and public space. . There seems to me a clear relationship

between looping musical improvisation within given limits, and the composition

of kinetic objects in time.

The complex system

based work of Peter Fischli and David Weiss, for example,

and the circular work of Arthur Ganson

can be seen along this same conceptual spectrum of composition.

The ideas remain the same, as does the longing to produce wonder in a modern

age—only the media has changed.

Imagined as a composotion without a performer, my most recent gallery pieces

use windows and immersive installations to transform kinetic lights and projections

into visual representations of the same sort of state-based organization inherent

in the music compositions which surround them. My desire is still to provoke

an experiential change in the viewer, but this time that change is created

through the optical illusions of 8bit controller programmed kinetic lighting

effects. In this case the composition remains buried inside the coding itself.

GRADUATE STUDY

If the task of a composer, as I see it, is to conceive, program, and perform

a guided experience I must learn what it means to compose not so much for people

for as perceptual systems. As I ask my reader (and myself), in the liner notes

for Impossible Duets,

“What does music do, and how does it work?”

This

is not meant as a Cagean inquiry into the sonic specificity of music itself,

but rather an invitation to consider how music mediates the relation between

the human and animal, between organic and inorganic, between worlds both

built and natural. Does the ineffable enchantment of organized sounds

bear a familial

resemblance to the chaotic forms of fire? Or else to the mountain ridges

and schools of translucent fish by which we are so mysteriously and

inexorably

compelled? What could evolutionary biology and cognitive science teach us

about the Classical symphony

composition that extent theoretical investigations have not?

Graduate study at Columbia University would allow me to refine the conceptual

tools necessary to cultivate my potential as an composer and knowledge creator,

specifically by allowing me to synthesize the diverse interests I have pursued

over the

years

within

the context of a rigorous intellectual community. The opportunity to learn

from professors like Fred Lerdahl, Bradford Garton, and Tristan Murail, and

to collaborate with those scientists and musicians engaged in the investigation

of the mind and its relationship to musical language, would have an immense

and transformative effect on my compositional and artistic practice. As an

artist who has drawn inspiration from many forms of media, I am excited by

the possibility of committing myself to the study and composition of chamber

and orchestral music, and to take part in the pioneering research into of

traditional forms for which Columbia’s Department of Music is celebrated.

I hope to invigorate my own work through a productive confrontation with

those musical

traditions which my own practice has hitherto deemphasized, and to use my

experimental methods to make provocative contributions to the scene of contemporary

music.

I have no doubt that our collaboration would be hugely significant- and

exciting- for us both.